By Tom Houseman, Oak Park Regional Housing Center Summer Intern

A poverty trap is any aspect of a person’s life that creates and reinforces poverty for themselves and their family, often persisting to the next generation. One of the most commonly identified poverty traps in modern America is living in a neighborhood in which a high percentage of people are also living in poverty. These neighborhoods frequently have underperforming schools, poor healthcare access, minimal job access and high crime rates. For these reasons, it is difficult for residents to create a better life for themselves and provide opportunities to their children.

A poverty trap is any aspect of a person’s life that creates and reinforces poverty for themselves and their family, often persisting to the next generation. One of the most commonly identified poverty traps in modern America is living in a neighborhood in which a high percentage of people are also living in poverty. These neighborhoods frequently have underperforming schools, poor healthcare access, minimal job access and high crime rates. For these reasons, it is difficult for residents to create a better life for themselves and provide opportunities to their children.

As much as people like to think that we are living in a society no longer defined by racial segregation, this is simply not the case. Ever since the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was signed by Congress, banning the use of discriminatory practices by the real estate and mortgage industries, the drop in the levels of racial segregation in American cities and neighborhoods has been frustratingly slow. The average white person in metropolitan America lives in a neighborhood that is 75% white, while a typical African American lives in a neighborhood that is only 35% white (not much different from 1940) and as much as 45% black.

Chicago is one of the most extreme examples of the endurance of urban racial segregation. Of the 77 Chicago neighborhoods, 20 have a black population of at least 90% and 33 have a black population of less than 10%. Blacks and whites in Chicago are so clustered that 72% of Black or White residents would have to move to a different census tract to even out the numbers.

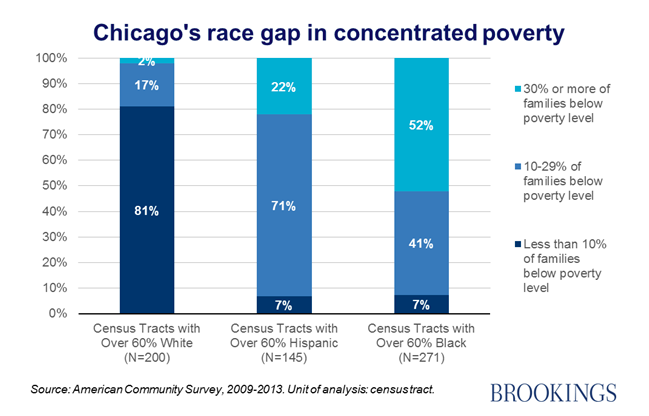

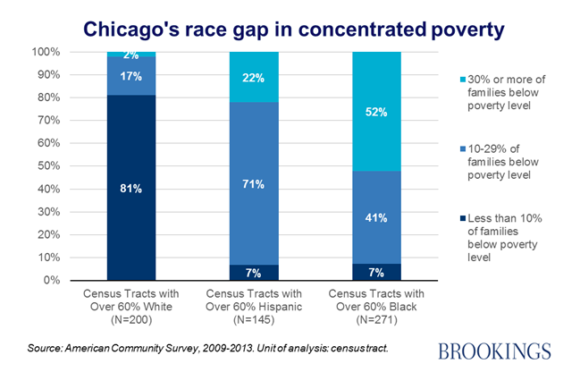

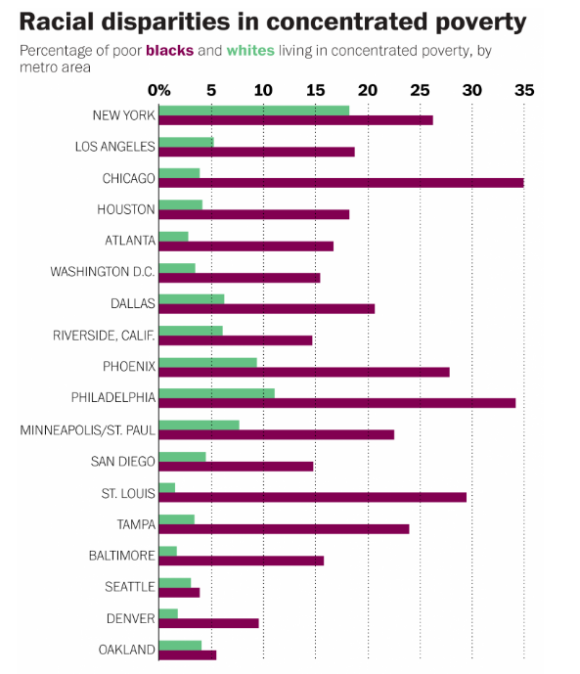

Segregation is, without a doubt, one of the most persistent and harmful poverty traps; not only is it as damaging as high-density poverty, but the two are deeply intertwined, especially in cities. In Chicago, just over half of census tracts with a majority black population have more than 30% of families living in poverty, while only 2% of predominantly white census tracts have that high a percentage of families in poverty. At the same time, only 7% of majority black tracts have fewer than 10% of families in poverty, while 81% of majority white tracts do.

One of the reasons that segregation and high-density poverty are so persistent, and so connected, is that highly segregated neighborhoods lead to high levels of unemployment for residents, an effect that is clear when seeing how much higher employment levels are for black Americans than white ones. Despite a narrowing of the black-white education gap, the black-white unemployment gap remained largely unchanged throughout both the boom years of the 1990s and the recessions that plagued the 2000s.

In cities with high levels of segregation, like Washington D.C., Detroit, and Chicago, finding and keeping a job is a struggle for minority residents. Even when controlling for the poverty rates of a neighborhood, the percentage of black people who are unemployed increases as the level of residential segregation increases, and the probability of employment in low-segregated metro areas is significantly different from medium-and high-segregated metro areas, an effect that is not evident for white people. In fact, in metropolitan areas where residential segregation is low, blacks with more education and experience are more likely to be employed than similar whites.

In cities with high levels of segregation, like Washington D.C., Detroit, and Chicago, finding and keeping a job is a struggle for minority residents. Even when controlling for the poverty rates of a neighborhood, the percentage of black people who are unemployed increases as the level of residential segregation increases, and the probability of employment in low-segregated metro areas is significantly different from medium-and high-segregated metro areas, an effect that is not evident for white people. In fact, in metropolitan areas where residential segregation is low, blacks with more education and experience are more likely to be employed than similar whites.

One of the most important factors in understanding how segregation creates unemployment and poverty is an effect known as “spatial mismatch.” For decades, the primary source of employment in cities, especially for the poor, was manufacturing, an industry so dominated that an entire region, “the rust belt,” was named in its honor. The urban poor crowded into the center of cities, willing to live in densely populated areas plagued by health issues to maintain easy access to jobs. Over the last fifty years, as manufacturing jobs were either lost to automation or shipped overseas, the primary source of jobs in metropolitan areas moved to the outer edge and the suburbs, but the poor, especially poor minorities barred from moving into certain neighborhoods, were not able to follow the jobs.

If a person has been unable to move out of the center of the city, where there are no jobs, their employment options will be severely limited. As a result, those who live in neighborhoods with higher levels of spatial accessibility to low-skill jobs have lower levels of unemployment than those who live in neighborhoods with lower levels of accessibility. The higher the level of sprawl in a metropolitan area – the more spread out and less dense a city is – the worse this effect is. Sprawl is noted as a major hindrance to employment, as blacks are more geographically isolated from jobs in high job-sprawl areas regardless of region, metropolitan area size, and their share of metropolitan population.

Other effects of spatial mismatch and urban sprawl on employment include:

- Making it much harder for women employed in childcare and housework to find and get to jobs

- Forcing employed people to spend more time and money on commutes, leaving them with fewer opportunities to pursue education or spend time with their families

- Increasing reliance on cars, which not only increases pollution in cities, but means that losing access to your car is the equivalent of losing your job

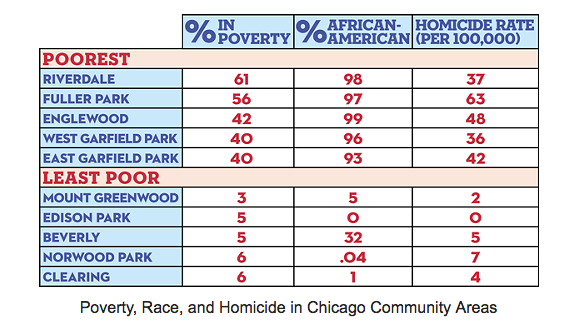

Obviously, the poverty traps created and reinforced in part by racial segregation are a serious problem for American cities, not just for the immediate effects they have on the community, but also for the secondary effects felt by all of society. One of the most obvious impacts of high-density poverty is its relationship with crime. Neighborhoods with consistently high rates of poverty create environments with much higher crime rates than in the general population. In fact, even being poor is not seen as an adequate predictor of criminal behavior unless the person lives in a high-poverty area.

Obviously, the poverty traps created and reinforced in part by racial segregation are a serious problem for American cities, not just for the immediate effects they have on the community, but also for the secondary effects felt by all of society. One of the most obvious impacts of high-density poverty is its relationship with crime. Neighborhoods with consistently high rates of poverty create environments with much higher crime rates than in the general population. In fact, even being poor is not seen as an adequate predictor of criminal behavior unless the person lives in a high-poverty area.

One of the groups for whom this connection between poverty and crime is strongest is youth, a dangerous trend that will make it even harder to lift future generations out of poverty. It has become clear that when it becomes harder for teenagers to get and maintain jobs they are more likely to turn to crime, either as a means to monetary gain or as a way to become part of a stable social circle. Either way, providing employment access to young people is one of the best ways to not just help them economically advance, but to also help them avoid criminal activity that could severely damage their long-term prospects.

If being trapped in poverty increases the likelihood of criminal activity, what is the effect of being removed from a high-poverty area? One of the primary concerns surrounding public housing relocation is that crime from poor neighborhoods will be brought into new parts of cities along with the new residents, but results have indicated that this is not the case. Not only has it been shown that crime rates decrease in neighborhoods that experienced drops in the number of residents living in poverty, but crime rates also typically drop in neighborhoods that receive small numbers of public housing residents.

When poor people lack access to high-quality jobs, easy and affordable transportation, and a sense of public safety, there is very little that will change to allow them to work their way out of poverty. Segregation only exacerbates these problems, making it dramatically more difficult to end the cycle of poverty that has plagued some neighborhoods for over a century.

High unemployment caused by segregation is bad for everyone, not just minorities and the poor. When people need to spend more time getting to work it increases traffic and pollution, and makes the entire city less efficient. When employment drops, people become more reliant on the social safety net, increasing the amount that the government must spend on welfare programs. When crime rates increase, everyone is less safe. Segregation, poverty, and crime are not just issues that affect poor people, but societal plagues with deeply felt ramifications. If society is serious about tackling poverty, one of the first topics that will have to be addressed is how to more effectively integrate our neighborhoods and cities.

REFERENCES

- Logan, John R and Brian J. Stults (2011) The Persistence of Segregation in the Metropolis: New Findings from the 2010 Census

- Lichter, Daniel T, Domenico Parisi and Michael C. Taquino (2012) The Geography of Exclusion: Race, Segregation, and Concentrated Poverty, Social Problems, 59:3

- Capps, Kristen (2014) The Housing Bubble Also Left Our Neighborhoods More Segregated, CityLab

- Luhby, Tami (2016) Chicago: America’s Most Segregated City, CNN

- Parks, Virginia (2004) Access to Work: The Effects of Spatial and Social Accessibility on Unemployment for Native-Born Black and Immigrant Women in Los Angeles, Economic Geography, 80:2

- Stoll, Michael (2005) Job Sprawl and the Spatial Mismatch between Blacks and Jobs, Brookings

- vonLockette, Niki Dickerson (2010) The Impact of Metropolitan Residential Segregation on the Employment Chances of Blacks and Whites in the United States, City & Community, 9:3

- Quillian, Lincoln (2012) Segregation and Poverty Concentration: The Role of Three Segregations, American Sociological Review, 77:3

- Sharkey, Patrick (2013) Rich Neighborhood, Poor Neighborhood: How Segregation Threatens Social Mobility, Brookings

- Badger, Emily (2013) Why Segregation is Bad for Everyone, CityLab

- Chetty, Raj et Al (2014)Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the U.S., American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 104:5

- Butler, Stuart M. and Jonathan Grabinsky (2015) Segregation and Concentrated Poverty in the Nation’s Capital, Brookings

- Popkin, Susan J. et. Al (2012) Public Housing Transformation and Crime: Making the Case for Responsible Relocation, Urban Wire

- Steinberg, Sarah Ayres (2013) The High Cost of Youth Unemployment, Reuters

- Badger, Emily (2015) Black Poverty Differs from White Poverty, The Washington Post

- Covert, Bryce (2015) How a Poor Neighborhood Becomes a Trap, ThinkProgress