Oak Park Regional Housing Center History – As part of Oak Park’s efforts to address issues of integration and diversity since the 1960s, the Oak Park Regional Housing Center has been a major player in working to welcome minorities to the Village while avoiding resegregation that has so often occurred in many American urban neighborhoods and communities. Even as times and issues have changed, the Housing Center continues to serve Oak Park and remains an important component of Oak Park’s present and future.

Following World War II, neighborhood after neighborhood on Chicago’s west side experienced resegregation, changing racially from white to black. This was not a natural phenomenon, but the result of redlining, the refusal of financial institutions to lend in neighborhoods they considered “risky;” blockbusting, a real estate practice that promoted panic in neighborhoods when an African-American family moved in; and the lack of action from city government.”

Neighborhoods often changed from white to black in a matter of weeks. By 1960 resegregation was occurring in the Austin neighborhood adjacent to Oak Park. Some academic “experts” predicted that within a few years Oak Park would also begin to resegregate. That this did not happen was not due to chance, but rather to a community-wide effort involving an active citizenry, a few very dedicated individuals, one lender willing to invest in Oak Park, and a Village government that addressed the issue straight on. It was in this context that the Oak Park Housing Center came into being.

The 1960s were a time of turmoil and in Oak Park turmoil focused on the potential for racial change and resegregation. According to the 1960 census 57 African-Americans lived in Oak Park, primarily a declining servant population to Oak Park’s wealthier families. But in the mid-1960s new Black families began to purchase homes in Oak Park. Lenders began redlining the Village and it looked like racial change might follow the pattern well established on Chicago’s west side.

The Village government began taking steps in response, creating a Community Relations Commission in 1963 and a Residence Corporation in 1965 to deal with blighted homes. So-called “Hundreds Clubs” were established in 1968 to foster neighborhood cohesion and encourage home maintenance and improvement. (Today’s block parties, a legacy of these “Clubs”, informally serve the same purpose.) One lender, St. Paul Federal Savings and Loan, whose president lived in Oak Park, continued to lend to Oak Park home purchasers.

After weeks of heated debate, the Village Board passed a Fair Housing Ordinance in May of 1968, a month after the passage of the Federal Fair Housing Act. The Oak Park Ordinance prohibited discrimination in home and apartment advertising, home sales, rentals, and financing, as well as outlawing panic peddling. The Community Relations Commission was charged with enforcing the law, although it would not be staffed or have an office until 1970.

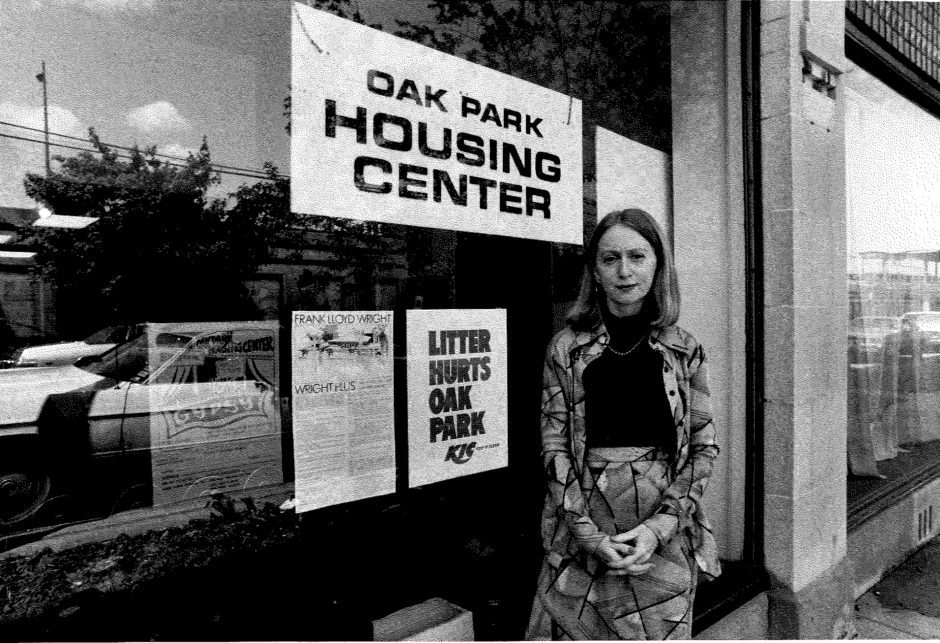

By 1970 Oak Park had positioned itself as an open community, declaring black families to be welcome. It had also taken some steps to discourage rapid racial change. But as of yet, it had no policies or procedures to ensure that no one section or the entire Village would resegregate. Fortunately, one citizen, Roberta “Bobbie” Raymond, stepped forward with the idea of the Oak Park Housing Center.

Bobbie Raymond’s plan was simple. Since multi-unit apartment buildings made up approximately half of Oak Park’s housing and since the turnover in renters could be quite rapid, renters and landlords would be the Housing Center’s focus. Center staff would match potential tenants with apartment units in ways that promoted integration while helping landlords find tenants for their vacant units. White apartment seekers would be encouraged and directed to units where it was felt that “white demand” was soft, while Black apartment seekers would be encouraged and directed to locations where few if any African-Americans were already living. Landlords who agreed to let the Center act as their “agent” would get help in renting their units and would not have to worry about their buildings resegregating.

The Housing Center opened in 1972 in the basement of the First Congregational church (now First United Church). While independent from the Village government, it has worked closely with the Village and has been funded by it. Raymond and subsequent directors have always tried to coordinate the Center’s work with Village programs. This was particularly the case when Sherlyn Reid was the head of the Community Relations Department (1977 – 1999). By informing clients that the Center’s goal is to promote integration and diversity and leaving the ultimate choice of where to locate up to the client the Center operates in compliance with fair housing laws. This counseling and referral program has been very successful in keeping Oak Park’s housing stock integrated.

The Oak Park Regional Housing Center has been a major element, but not the only one, in Oak Park’s efforts to become and remain integrated. Several initiatives were introduced in the 1970s. These included; a ban on for-sale signs passed by the Village Board in 1972 (later ruled unconstitutional but still voluntarily practiced today), an official diversity policy statement passed by the Village Board in 1973 and subsequently passed (and amended) by each new Village Board, a Village funded equity assurance program allowing homeowners to “insure” their homes against racial change, work by the Residence Corporation to purchase, rehabilitate, and sell multi-family buildings, and a reorganization of the Village’s elementary and middle schools drawing boundaries to promote diversity in each of the Village’s six elementary and two middle schools.

While the rental counseling and referral program remained at its core, the scope of the Housing Center expanded over the years. In 1977 it organized the Oak Park Exchange Congress, promoting Oak Park and sharing programs and policies with integrated suburbs throughout the U.S. In 1985 the Center began working with the Village on a Diversity Assurance Program, providing loans and technical assistance to landlords who agreed to market their units through the Housing Center. In 1992 the Center initiated the New Directions Program (Apartments West) expanding choices for its clients throughout the western suburbs. With this came the name change, to the Oak Park Regional Housing Center. Rob Breymaier, the Center’s Director from 2006 to 2018, reoriented the New Directions program by establishing a short-lived program in Berwyn, creating the West Cook Homeownership Center, and working with several Austin organizations on community and housing issues.

Much has changed since Oak Park and the Housing Center began working toward integration in the Village. Integration is no longer just a black and white issue. The citizens and government of Oak Park continue to struggle with what it means to be a diverse community. Threats of resegregation may not be as obvious, but they have not gone away. Bobbie Raymond was always quick to point out that as long as racial discrimination exists, work to maintain integration is necessary. Today Oak Park faces an ongoing task to promote diversity and to maintain its integrated neighborhoods. With community support, the Housing Center will be there doing its part to ensure a fair, equitable, and integrated Village.

William Peterman

The Oak Park Regional Housing Center history was written by William Peterman, a retired professor of Urban Geography at Chicago State University and Oak Park resident. He is also a former board member of the Oak Park Regional Housing Center.