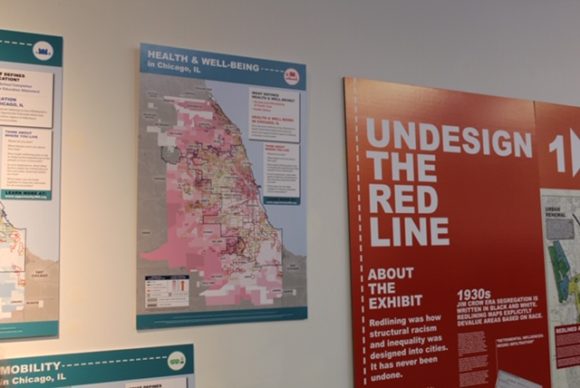

On April 25, the Oak Park Regional Housing Center, Chicago Fair Housing Alliance, and Enterprise Community Partners sponsored the Assessment of Fair Housing: Understanding Our History, Strengthening Our Communities conversation at the National Fair Housing Museum. The event featured nationally-renowned sociologist, author, and expert on race and inequality, Professor George Lipsitz, who provided a lecture on the history of housing discrimination and segregation, and its impact on today’s society. Group discussions were also held on current economic and social conditions, past efforts to advance fair housing, and solutions to inform the AFH process and create stronger communities throughout Cook County. Participants also received a private tour of the exhibit, UnDesign the Redline, which will be at the museum until May 31.

Lipsitz informed the assembled audience of housing advocates, and municipal/public housing authority leaders, how the U.S. government housing policy of redlining condemned black communities to a death sentence. Redlining was when black Americans were expressly excluded by the federal government from access to home loans that would enable them to acquire assets that appreciated in value and could be passed down across generations. Instead, black American communities were subject to a policy that meant loans were not to be made available to improve or buy buildings in or out of the neighborhood, which allowed white speculators to buy up properties and subdivide them into tenants, where they were allowed to let their buildings deteriorate and charge higher rents. These speculators now had access to a captive, artificially constrained part of the housing market, forced to pay higher prices, and crowded into an area abandoned by the police, and municipal services.

From 1934 to the 1968, black American taxpayers helped subsidize loans for white Americans to buy houses in the suburbs or all-white urban neighborhoods, while being denied those same loans. Everyone who designed those redlined maps are no longer here, Lipsitz stated, but they still exert enormous power over almost everything in society. “Races and places are related, the redlining maps of Chicago in 1939 pair almost exactly with the opportunities and life chances in Chicago in 2019. Almost two-thirds of the neighborhoods that were redlined are still occupied by people who are in their 2nd, 3rd or 4th generation in a poverty environment.

He cited a study by sociologist Douglas Massey, which stated that the main driver of concentrated poverty is housing discrimination, where poor whites are able to move to high opportunity areas, where they are able to get apartments, stores with better food, and not worry about being pulled over while driving in their neighborhood. Residential racial segregation concentrates poverty, which means that even middle class blacks can’t move away from the fate of poor blacks. When it comes to cleaning up toxic waste, middle class blacks live in places that are more polluted than where the poorest white people live. This creates a concentrated poverty that happens across generations. “It is not that we want fair housing in a society that is also incidentally plagued by inequality, but rather that unfair housing is the originator and perpetuator of this inequality,” said Lipsitz.

To undesign the redline, Lipsitz stated, “We are not simply exposing long-suppressed grievances and acts of inhumanity, we are trying to revisit the past in order to break its chains. We are trying to become fully aware and have presence of mind of what exists in the present by looking at things in retrospect to understand that the things that were done by humans can be undone by humans. Part of our job is to take this evidence and bring it to people so that they can democratically participate in shaping this society by seeing clearly, by looking at their street and how it came to be, by thinking about their opportunities.”